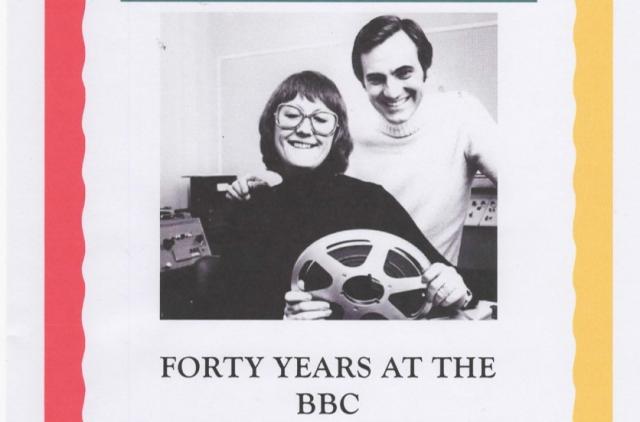

TALK – FORTY YEARS AT THE BBC

©Frances and Jim Lloyd. Reproduced by permission. Not to be reproduced elsewhere without the written permission of the copyright holders.

JIM: WARM-UP

Introduces FRANCES

FRANCES:

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Thank you for coming. It’s a pleasure to be with you but I have to start with a confession. Jim and I have called this entertainment “Forty Years at the BBC”. Actually it was only thirty-nine and a bit but somehow thirty-nine and a bit years at the BBC doesn’t have the same ring to it so I hope you’ll forgive our little exaggeration.

Yes – thirty-nine and a bit years… during which I rose from a clerk-typist to the Controller of the Station of the Year – BBC Radio 2 – and I did this with no visible means of support other than six O Levels and a swimming certificate.

JIM:

A few months before Frances retired she received the Basca Gold Award for services to popular music. The citation from Liz Forgan – then Managing Director, BBC Radio – read:

“Frances Line has been more than the Controller of Radio Two. She has been its heart, its soul and its voice. The knowledge of popular music Frances carries round in her head is a benchmark for programme makers and presenters. All of us at BBC Radio salute Frances’ contribution to musical life in Britain”

FRANCES:

This is an extract from a listener’s letter which I received a few days later:

(READ)

“Old Boiler. So now we know why we have to suffer such awful programmes. It’s all been so you can get an award.

It’s a pity you don’t produce the programmes most of us want.

Entertainment and good music. Both are in short supply on Radio Two thanks to your rotten taste. You are bloody useless”

JIM:

To go back to the very beginning:

On 20thAugust 1957 Frances received a letter from a BBC Establishment Officer:

We have pleasure in offering you a post on the unestablished Staff as a Grade S.3 Shorthand Typist at a salary of Six Pounds Thirteen Shillings per week. When you are regarded as fully capable of undertaking secretarial duties on your own initiative and have passed the Proficiency Test you will be eligible for promotion to Grade S.4.

The Proficiency Test in Shorthand and Typing was almost her downfall. A month after she joined the BBC a report on Frances’ progress read:

A steady worker who wastes no time in getting down to a job and turns out neat material though her speeds are not very high.

This is just a small selection from the memos about Frances’ Proficiency Test. They are still on file at the BBC.

In March 1958 her Establishment Officer reported:

Miss Line tells me that she does not, at the moment, feel qualified to take the Proficiency Test. She will let me know when she wishes to do so.

26thSeptember. From Head of Training School to Establishment Officer:

This is to confirm that owing to illness Miss Line missed the second part of her Proficiency Test. She will be attending next Thursday.

5thOctober. From Head of Training School to Frances Line.

The results of the Proficiency Test for Junior Secretaries are now available – I very much regret to tell you that you were not successful.

9thOctober. Establishment Officer to Head of Training.

Thank you for your report of Miss Line’s recent Proficiency Test – she was not surprised at her failure.

2nd December. Frances Line to Establishment Officer.

I should be very grateful if you would arrange for me to re-take the parts of my Proficiency Test which I failed at my first attempt. And there’s a little addendum here. Please note that I am taking Bisque Leave on Tuesday, 9thDecember.

Perhaps you should explain what Bisque leave is.

FRANCES

Bisque is a wonderful word, it actually comes from the game of croquet and it means “a free shot”. In BBC terms it’s an odd day’s leave that you can take at short notice. It was explained to me that it saved killing off your Auntie Flo every time you wanted a day off for Christmas shopping.

JIM:

Anyway, back to the saga:

17thFebruary. Establishment Officer to Head of Training.

Miss Line was most grateful for the Test Papers and I will let you know when she wishes to have another attempt after further practice.

And finally, the great day arrived – 14th June 1959. Head of Training to Frances Line.

The results of the Proficiency Tests for Junior Secretaries which you took on 22nd September 1958, 2nd October 1958, 27thJanuary 1959 and 9th June 1959 are now available and I am glad to tell you that you have Passed.

That very week her money went up to 9-5s-6d.

FRANCES:

Not an overnight success, but I got there in the end. In a BBC bristling with graduates, I was almost always the odd one out. In the end I was running the most popular station in the country yet I was the only Network Controller without a degree. That’s not something I’m particularly proud of, by the way, I just feel that my lack of higher education meant I was able to identify with ordinary listeners. Largely I liked what they liked and that made the task of commissioning hundreds of programmes a year that bit easier.

One of the extraordinary things about Radio 2 is its breadth of appeal. On the one hand, I am reliably informed that the Queen Mother favours Radio 2 – and on the other we have many captive listeners. Among them the notorious Kray Twins who confessed to being listeners in the News of the World.

JIM:

It was Reggie Kray who wrote:

“We both love to listen to Radio Two. We’ve learned to appreciate another side of life. One of my favourites is Colin Berry of Radio Two… He’s a nice fellah.”

FRANCES:

I know Reggie still listens, because he’s regularly in correspondence with Colin Berry, and has quite firm views about Radio 2.

JIM:

But perhaps we should start at the beginning and share with you how Frances came to join the BBC.

She was born in Croydon in 1940 and spent her early years in nearby Norbury, attending Winterbourne Primary School where the school motto is – VINCAM:

FRANCES:

“I shall overcome”.

JIM:

From Winterbourne Frances went on to James Allen’s Girls School in Dulwich, known to the inmates as JAGS. She was a scholarship girl, the first to be accepted from Croydon.

She soon learned that JAGS girls were a breed apart. Hand-reared by dedicated staff who placed as much emphasis on social graces as on academic achievement, they were taught to mind their manners, to stand up straight and to speak properly.

FRANCES:

I remember that when the Queen visited Dulwich we were made to rehearse discreet “Hurrahs” – JAGS girls didn’t shout “hooray”. It was common.

I’m sure we all look back on our school days and the teachers who influenced us then. I always remember my challenging relationship with the biology teacher, Miss Fogg. She was given to telling little jokes which I didn’t find amusing and instead of smiling pleasantly like a good JAGS girl, it was my habit to fix her with a beady eye and solemn stare. One day she could stand it no longer. Taking me aside she chided me for my “damned supercilious expression” which she warned me would win me no friends in later life.

Miss Fogg nearly ruined my career. In later life, when faced with a hundred and fifty mutinous staff, my “damned supercilious expression” was often all that stood between me and disaster!

JIM:

When the time came to leave JAGS there was no thought of University for Frances. Miss Skinner, who doubled Geography and Careers, suggested that she should capitalise on her limited ability to draw neat maps and seek work in the Automobile Association.

But by this time she had decided what she was going to do.

FRANCES:

I was going to become a star of musical comedy.

Elocution, ballet and piano lessons had gone to my head. In addition, I was a regular visitor to seaside concert parties here in Eastbourne which I thought were wonderful. My family and I used to stay here every summer with my Auntie Belle and Uncle Ernest in Windermere Crescent, just off Seaside. The house is still there.

In fact I made my first stage appearance here in Eastbourne. Perhaps you saw me? It was in the theatre on the pier. I was the little girl who beat all the other children up on to the stage to help Sandy Powell bake the magic cake.

JIM:

Eastbourne Pier was followed by visits to theatres like Croydon Grand and Streatham Hill Theatre where she got really bitten by the show business bug. And then one evening her father asked Frances what she wanted to do when she left school. He got an unwelcome surprise.

FRANCES:

“I want to go into Show Business, Dad” I cried and I leaped up, positioned myself in front of the fireplace and treated my startled parents to an unaccompanied rendition of “Some Enchanted Evening”.

“Some enchanted evening – you may see a stranger – you may see a stranger across a crowded room… “

JIM:

Her father, a wily old Bank Manager, considered this proposition for a while. “What we need, old Poppy” he said, “is SHOW BUSINESS WITH A PENSION.”

“

FRANCES:

It had to be the BBC. We wrote off and got one of those marvellous forms that asks so many questions that it takes several hours to complete. It was more like joining MI5 than going into Show Business.

JIM:

Frances actually started with the Corporation in 1957 but when she first presented herself for interview she was still at school and arrived at Portland Place in her school hat, gloves in hand and sensible shoes on feet. A shiny-faced sixteen-year-old, devoid of make-up and not a bit like today’s confident young adults – but when asked how she saw her long-term future Frances replied that one day she hoped to be a producer.

FRANCES:

This provoked much mirth in the lady who was asking the questions. She made copious notes and ended with a one-line summary. As she turned away for a moment to answer the phone I used my highly developed skill for reading upside-down (vital to all who would make their way in the BBC) and saw it read “A NICE TYPE OF GEL ”. That was enough to get me in and I joined the BBC convinced that I was entering show business.

JIM:

Far from it. She spent her early days in a building with the Dickensian name of Bentinck House, Bolsover Street, filling out orders for bibs and braces for BBC firemen and typing out records of disciplinary interviews with drunken commissionaires.

FRANCES:

It was one such record of an interview that found my spelling wanting. One New Year’s Eve a BBC commissionaire had celebrated too well, had swung a punch at his manager and sworn at him – all this on BBC premises. This had to be documented – complete with verbatim quotes.

My boss sent for me to take dictation. It appeared the commissionaire had told his manager to “Bugger Off”. In those days, “NICE TYPES OF GELS” didn’t hear such words and – in order not to embarrass me – my boss wrote that bit down in his unreadable scrawl. I sent back the finished work with the offending word spelt B-U-G-G-A-R and had to type it all over again.

In those days it paid to know how to spell. There were no word processors then and no Tipp-Ex. It was all carbons, flimsies and good old fashioned erasers that made holes in the paper.

JIM:

The nearest Frances ever got to a programme in her first year was despatching contracts for potted palms for recordings of Grand Hotel.

But privately Frances was always in the studios. She has discovered something called The Ticket Unit which doled out free tickets for audience shows and – rain or shine – Frances was always first in the queue at the Paris, the Playhouse or the Concert Hall… all famous BBC studios at the time.

It was also around this time that Frances made her debut on Television. You may remember seeing her. You don’t… Give them a clue, Frances.

FRANCES:

Hand jives.

JIM:

Got it now? Yes – in the audience of 6.5. special.

(“Over the points, over the points, over the points, over the points…

FRANCES: The 6.5. Special’s coming down the line, the 6.5. Special right on time…”

JIM:

Every Saturday Frances was to be seen hand-jiving at the feet of Wally Whyton, Josephine Douglas and Pete Murray.

FRANCES:

Ah those were the days, in my circular skirt with all the stiff petticoats underneath. And my stilettos. I loved them and I’ve still got them.

They wouldn’t have done for the office though.

In those days there was a strict dress code for women at the BBC.

No trousers, never mind jeans! Skirts or dresses only – and they had to be of a modest length.

If you knelt down, they had to touch the floor and from time to time we were sent for to do just that – to kneel and have our hemlines checked!

Thirty years later when I was Head of Radio 2’s Music Department, we had a heat wave and the girls were coming into the office in the skimpiest tank tops and shorts which revealed yards of leg. When I suggested that this wasn’t quite right attire for the office, one of them complained to the Evening Standard and I found myself starring in a large article about draconian measures at the BBC!

JIM:

It was a very different BBC in the fifties. Here’s a memo from 1959. It’s from a producer to Frances’ Personnel Officer:

“Thank you for lending me Frances Line last week.”

FRANCES:

He made me sound like a library book.

JIM:

“She is intelligent, adaptable, unfussy, has a poise beyond her years and ornaments the office.”

FRANCES:

And I never DREAMED of complaining to the Evening Standard!

JIM:

In those days, Secretaries were seen and not heard and they addressed their bosses as “Mister” – which they invariably were. The occasional women had scaled the ladder during the war while the men were away but in the peaceful fifties they were not considered to have set any precedents. They simply worked their allotted span – and retired – to be replaced by fresh-faced young male graduates.

FRANCES:

Eventually I escaped from Administration and netted a job as a Production secretary in the old Light Programme.

That was more like it! I spent some time as second secretary on The Navy Lark and even did a short stint on the Billy Cotton Band Show.

At least I was in show business! I watched the other – very senior and experienced Secretaries – talking to the artists and calling some of them by their first names. I thought I’d give it go.

The vocalists with the Billy Cotton Band were Alan Breeze and Cathy Kaye and I thought she looked the more approachable. “May I get you a cup of coffee, Cathy?” I ventured. She looked me up and down. “It’s Miss Kaye to you”. So much for show business.

JIM:

Eventually Frances became Secretary to a man you may have heard of – Brian Matthew. In those days he was a BBC Producer.

As Brian’s Secretary she clicked her stopwatch on the pop programmes of the day – Saturday Club and Easy Beat – and even worked on a series with the Beatles.

FRANCES:

Though I regret to say that when an eager young researcher from Radio 1 pumped me for my memories for “The Beatles Story” all I could remember about those superstars was that they made paper darts out of my carefully typed scripts and threw them at each other. I resented it deeply!

However, not only have I got my stilettos but I’ve also got all my diaries across the years and I checked the entries for the Beatles period certain that I would find some amazing anecdotes. No such luck. Listen to this.

3rd April 1963

Worked with the Beatles all day. Then Terry [current boyfriend] took me for a drive in Dulwich Park where I had a nose bleed so we had to come home.

June 1st 1963

Went to the studio for Beatles recordings. Very busy in the office. Very rushed lunch. Changed the ribbon on my typewriter – what an effort.

Well – so much for the Beatles… second string to a typewriter ribbon!

But back to my career.

JIM:

Frances enjoyed working for Brian Matthew who – very unusually – not only produced programmes but presented them too. This meant that he was kept very busy – often trying to be in two places at once (behind the microphone and in the sound cubicle) and this provided her with ample opportunities to offer to take over some of his workload.

FRANCES:

Once I’d gained his confidence, he would, when particularly pressed, let me do things which weren’t really part of the Secretary’s job – like talking to the artists about what they were going to sing and picking the occasional record for the programme. I loved that of course – it was very exciting for a star-struck twenty-year-old – and followed him round watching his every move – just waiting and hoping for him to delegate something!

That’s really where I learned my skills, and I remember that on my twenty-first birthday – 22nd February 1961 – which was a Wednesday and an Easy Beat recording night – that Brian actually let me cast the whole show. That was a big thrill and I pored over the list of artists for hours – trying to be veryprofessional and dispassionate in my selection…. although I was able to use one of my favourite groups – Kenny Ball’s Jazzmen – as they were topping the charts at the time.

Quite early in our relationship, Brian gave me my first broadcast. All week long I studied the script and when the great day arrived stood at the microphone like a seasoned professional. Perhaps you heard me. It went like this: “Ere, Mum, it’s the Easy Beat Man”.

JIM:

That was exciting, wasn’t it? Let’s ask her to do it again so we get the full flavour…

FRANCES:

“Ere, Mum, it’s the Easy Beat Man”.

JIM: A star was born…

Slowly Frances rose through the Secretarial grades in radio but the time came when she could go no further. There was no prospect of a mere Secretary becoming a Producer. Frances had rather boldly put up one or two programme ideas which caused a mild flutter at her audacity but there were no takers. So she took herself off to television and became a Producer’s Assistant in Light Entertainment.

FRANCES:

There I worked on musical programmes and some light dramas. My claim to fame from those days is that I was the PA on the first ever edition of Top of the Pops. We brought the Rolling Stones live to the nation, from a converted church in Manchester – with camera one going up and down the nave.

JIM:

Perhaps we should explain what a PA does in television. Of course there’s all the usual administrative work such as making sure all the artists are contracted, booking the studios, making the travel arrangements, typing the camera scripts, ordering slides and captions, checking all the names on the closing roller, but most important of all is the studio work.

The PA sits next to the Director in the gallery, looking at anything up to a dozen television screens – one for each camera, others for film, video and so on, and the most important of all which is ‘studio output’ – or what the viewer sees.

And while the Director is watching the overall picture, it’s the PA who calls the shots – telling the camera men and floor manager what the viewer is seeing on the screen and lining up the next picture. All the cameras have numbers so you address the cameramen by their numbers…. camera one, two etc. That sounds pretty simple but what you have to remember is that while the PA is calling the shots on a live programme – all hell is breaking loose!

FRANCES:

Right. So you have to shout – something like this:

“On you three – two next for the close-up – stand by four for the long shot, clear one…” or whatever.

I’d got pretty used to this by the time I came to work on a programme which is very much a part of television history – Juke Box Jury.

Do you remember that, with David Jacobs and “Hello there. Tell us panel – is it a Hit or a Miss?” I was the PA on that for quite a while at a time when the series was used as a training ground for new young Directors. As the resident PA, I had to hold their hand while they got their first experience of a real, live programme. It was pretty hairy at times, I can tell you!

Through Juke Box Jury I met all sorts and I particularly remember one fresh faced youth who came to the BBC straight from university with a degree in biology. I took him through the rudiments of directing the show and we became firm friends.

His name was Jim Moir and thirty years later I found myself taking him through the rudiments of running Radio 2, because he succeeded me as Controller.

These were exciting times and I moved around quite a bit from show to show…. some of them very famous in their time. For instance I worked on Z-Cars then on the P.G. Wodehouse series Blandings Castle which starred Ralph Richardson as Lord Emsworth. He was quite marvellous and tended to turn up for filming on his motor bike! We filmed it at Penshurst Place and feared for his safety daily – the Producer was always relieved when the last shot was in the can!

From time to time I had to telephone P.G. Wodehouse himself at his home in America and there were very strict rules about that. He was a great soap opera fan and there was a little list of times on the wall when he would or wouldn’t take calls. Certainly he would brook no interruption during the American equivalent of East Enders!

Life in television was exciting and full of variety. I had a great time on a series called Meet The Wife which starred Thora Hird and Freddie Frinton – two great troopers playing good broad humour – and then, in contrast, I worked with the epitome of sophistication, Duke Ellington, on Jazz 625. He was absolutely charming and made me feel like a Queen. I remember he wore a very distinctive perfume and when I shook hands with him it lingered for hours afterwards. Very suave.

Musical productions became my forte and I became PA to an American Musical Director called Buddy Bregman who arrived at the BBC “hot” from having made several albums with Ella Fitzgerald. We worked together on a series called International Cabaret which starred such luminaries as Juliet Prowse, Nancy Wilson… and Mel Tormé. And it was Mel Tormé who nearly brought my career to an untimely end.

JIM:

Like all major artists he had his own musical arrangements, which he had brought over from America for the programme. After the show he flew straight off to Copenhagen where he was due to appear at the Tivoli Gardens. His music was supposed to go with him, but unfortunately it didn’t. Even more unfortunately the only contact phone numbers he had were Frances’ office number – and her home number.

FRANCES:

And here’s a tip. Never, ever give an artist your home phone number.

JIM:

Somehow he’d convinced himself that it was all Frances’ fault – or at least her responsibility. And so the moment he arrived in Copenhagen he started ringing her, first in the office and – as day turned into night – at home.

FRANCES:

Even though I had done all I could, he felt it wasn’t enough and said he was going to ring every hour on the hour until I found his music. And he did, getting more and more irate with every call: his language certainly wasn’t the sort of thing that should be heard by “A NICE TYPE OF GEL”. By one o’clock in the morning my family had had enough. My father took the call told and asked him to stop bothering his daughter. I remember Dad said: “We’re going to bed now, Mr Tormé – and I suggest you do the same”.

Mr Tormé told my father that his daughter would never work in show business again.

JIM:

Fortunately Mr. Tormé was wrong.

Back in the sixties at the BBC there were very few women in high places in television. They were found behind typewriters, in the make-up and wardrobe departments and, very occasionally, vision mixing. But women couldn’t aspire to be television directors because directors had to have experience as floor managers. And women couldn’t be floor managers because floor managers worked with scene crews and scene crews used colourful language –

FRANCES:

Not the sort of thing that should be heard by “A NICE TYPE OF GEL”!

So – there was no through road in television and I came back to my first love – to radio – and I’m very glad I did. Radio was leading the way – as it so often does – and was quietly giving all sorts of chances to women.

In radio,

after years of watching male producers at work – and sometimes doing it for

them, female secretaries were being encouraged to train for production

themselves. Women studio managers were to be seen, balancing and recording

music sessions. And what’s more, as they clambered about, setting out mics and

moving loud-speakers, they were wearing trousers. These skirts “of a modest

length” were no good when you were up a ladder adjusting a microphone. A bright

new era was dawning!

JIM:

So Frances went back to radio as one of the first of the new breed of women producers. And although this was a step in the right direction it wasn’t quite the great breakthrough that it seemed. She found that she was one of six new producers – three were women and three were men. There were three permanent staff posts and three temporary posts and guess what? The three permanent posts went to men and the three temporary posts went to women. This wasn’t a coincidence, it was done on the grounds that the men were likely to have families, while the women had only themselves to support and anyway would probably get married!

FRANCES:

I became a producer in the last glow of the golden days of Radio. The old Light Programme – the days of really funny comedy, of live music and massive listening figures. The days when radio was king.

One of the first jobs given to a new producer was a programme you’ll all have heard of, I’m sure – Music While You Work.

It was hair-raising because it was live and quite early in the morning when you consider that it all had to be rehearsed before transmission and musicians are not exactly morning people. The slot was thirty minutes and you used to have to work out with the Musical Director a cue which he could clearly see at one minute to go so that he could get into the signature tune. Some experienced band-leaders could do wonders and wind the whole thing up very elegantly into “Calling all Workers” which was the name of the signature tune. Others would be half way through – say – “Begin the Beguine” and they’d panic and crash down the baton and the band would lurch into the closing routine and the programme would come out early with subsequent reprimands from high places!

Live radio was fun though. Much of it is still live but techniques are so much more sophisticated now that there are far fewer mistakes.

JIM:

Frances worked with all the big musical names of the time – Victor Sylvester, Edmundo Ros, The Oscar Rabin Band, Cyril Stapleton, Acker Bilk –

and then she me. I expect you’d wondered what I was doing here.

Well – I’ll tell you after the interval.

INTERVAL

JIM:

Welcome back. You’ll remember that before the interval, I was about to tell you how Frances and I met.

FRANCES:

But first, to go back a bit before that fateful day… Jim started life as an actor. He trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama, which in those days was housed in the Royal Albert Hall – whenever we go there he gets quite dewy-eyed about the building. He spent three years there alongside enthusiastic young drama students like Jeremy Brett, Mary Ure and Wendy Craig.

JIM:

Another of my fellow-students was Paddy Green – Patricia Green. You may not recognise the name but I’m sure you’re familiar with the voice. Shortly after leaving Central Paddy got her big break with what was then a new radio soap called The Archers. She joined the cast to play Jill Archer, the young daughter of the family – and is still playing Jill Archer – now the matriarch of the family.

As you probably know, The Archers is produced in Birmingham, and when my programme was moved to Birmingham about ten years ago I saw her in the canteen – after a gap of nearly thirty years. I always remembered Paddy at drama school having wonderful long black hair, so I was surprised to see that her hair was now a very distinguished silver. I said: “Hullo, Paddy, remember me?”; “Jimmy Lloyd” she said. “Your hair’s gone grey”.

FRANCES:

When Jim left Central School he went and worked in rep, as young actors did in those days. He even did a season here in Eastbourne – in 1957. With the Michael Gover players … Does anyone remember him?

JIM:

It was before I had grey hair…

FRANCES:

When I found out that he’d been in rep here I went along to the reference library and dug out the old copies of the Eastbourne Herald. And sure enough, there were his notices. This for an Ivor Novello play called I Lived With You:

Jan.30th1957:

James Lloyd – in Ivor Novello’s own part as the Prince – sailed through this terrific role like an old stager, His approach to the part and his understanding of the complex character he has to portray mark out Mr. Lloyd as an actor of quality.

JIM:

A star was born…

FRANCES:

And this – on January 23rd 1957. The play was The Man Upstairs:

James Lloyd makes but a brief appearance – and very uncanny he is too.

JIM:

She never lets me forget that word “uncanny”.

As well as knocking them cold in Eastbourne I did various rep seasons, some films and quite a bit of television, in shows like Emergency Ward Ten and No Hiding Place.

Then I got my lucky break. I went along to audition for a show that was being put on by two big impresarios at that time – George and Alfred Black. And after I’d given them my Chorus from Henry V and a bit of Pinter they took me to one side and started asking me questions about current affairs and politics – which I thought a bit odd. But it turned out that they were just about to open a new television station – Tyne Tees Television in Newcastle, and they were desperately short of an announcer. They asked me if I would go up to Newcastle for a camera test.

Now in those days you didn’t say “no” to George and Alfred Black, but the last thing I wanted to do was go and live in Newcastle. So I went for the camera test and did my best not to get it – I was very offhand about the whole thing. And, of course I got it.

FRANCES:

Jim spent two years in Newcastle, then moved to the Midlands and went freelance, working on everything from Come Dancing to Songs of Praise. I remember first seeing him, long before we met, on Sunday nights while watching Sunday Night at the London Palladium with my family. Jim was the in-vision Continuity Announcer and, if the programme (which was live) under-ran, we had several minutes in his company while he told us all the programmes coming up that night and – occasionally, when timings went seriously awry – all the programmes coming up that week!

JIM:

Round about that time I was working on one of the first chat shows. It was called Gazette and went out from Manchester. It was the height of Beatlemania when everything good seemed to be coming out of Liverpool and we used to have a folk group called The Spinners on the show. And it was The Spinners who got me interested in folk music. They told me there were these places called folk clubs, so I started going along to them around Northamptonshire, where I was living at the time.

I liked the music but – coming from the theatre – I thought the way it was presented was terrible, so I started my own folk club and did revolutionary things – like standing the singers on beer crates so you could see them.

This was a bad thing – selling out, degrading, commercial… However, people used to come along every week, and soon I was running out of acts. So I started booking them through an agency called Folk Directions, which I soon found out was run by a former fellow-student at drama school – Roy Guest.

FRANCES:

When Jim and Roy left Central School – while everyone else (Jim included) went into the theatre – Roy took his guitar and went off to New York and started singing in the Greenwich Village coffee houses.

There he met rising young singers like Paul Simon, Judy Collins and Tom Paxton.

Eventually he came back to England and set up Folk Directions, partly to bring over these young singers to appear in the British folk clubs that were springing up around the country.

JIM:

Well, Roy came up to stay one weekend and by Sunday evening I found that I had bought half of Folk Directions. It was the one time in my life when I was making more money than I actually needed, and I knew what capitalists do. You put your money into someone else’s business, sit back and let them do all the work, and you cream off the profits.

FRANCES:

Sadly, it didn’t work like that. Not having a wily old bank manager as a father, Jim didn’t know the first rule of show business – don’t put money into show business.

Very soon he had to get actively involved in Folk Directions to stop all his hard earned savings from disappearing. So Jim – the actor – Jim, the television presenter, became Jim – the impresario.

JIM:

At Folk Directions we put on the concert tours by people like Tom Paxton, Judy Collins and Buffy St Marie, as well as new English bands – like Fairport Convention. I remember we did the first tour by Simon and Garfunkel, just at the time of their Sounds Of Silence album, which became a world-wide multi-million seller. To tell you how little known they were then, they played to a full house at the Royal Albert Hall, half a house at Birmingham Town Hall, and a couple of hundred people in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall. Word hadn’t got up the motorway. At that time I’m not sure there was a motorway.

FRANCES:

I remember going to one of Jim’s presentations. It was the Theodorakis’ ensemble. Mikis Theodorakis was the Greek composer who wrote “Zorba’s Dance”. I went with my Dad – the wily old Bank Manager– and it was a terrific evening and we all ended up Zorba dancing in the aisles.

JIM:

Eventually, because I knew a bit about broadcasting and a bit about folk music I was invited to join a new radio programme called Country Meets Folk, which was hosted by Wally Whyton – now, alas, no longer with us. He was a really good friend for over thirty years and we both miss him.

Country Meets Folk ran for over six years, but soon after it started the producer phoned me to ask if I could think of an idea for another folk programme. I came up with something called My Kind of Folk, and after a few days he came back and said that Radio 2 would take the idea but that he wouldn’t be producing it. The producer would be Frances Line – a new, young recruit who’d just come over from television. I remember him saying: “You’ll like her – she’s been working on Top of the Pops”.

Well the last thing I wanted was some girl who’d been working on Top of the Pops interfering with my lovely folk programme.

FRANCES:

And the last thing I wanted was some hairy folkie interfering with MY lovely folk programme. But I thought the first thing to do was to meet him and see what I was up against, so I rang Jim and asked him to come to my office.

JIM:

So there I was in Aeolian Hall in New Bond Street – a wonderfully historic building in Mayfair – alas no longer owned by the BBC but by Sotheby’s, the Auctioneers. Anyway, there I was and I found the office with her name on the door, knocked and went in – and I saw two women sitting behind typewriters, an older one and a younger one. Then I uttered the words that changed my life: “Which of you ladies is Frances Line?”

[And]

FRANCES:

I said it was me.

JIM:

Which is just as well or I’d have ended up being Mr Joyce Sambles. Joyce was Frances’ Secretary.

I think the early days of our relationship can best be described as “stormy”.

FRANCES:

I couldn’t stand the sight of him and worked very hard to get him off the show. And you were doing the same with me, weren’t you?

JIM:

Well, yes.

FRANCES:

But eventually we found we worked extremely well together and after that we created a whole series of folk programmes for all four radio Networks, putting the traditional music of the British Isles firmly on the BBC agenda.

Not only did we WORK well together but we developed a harmonious private life. So much so that we got married back in 1972 and shall be celebrating our Silver Wedding later this year. I still have my wedding dress – along with the diaries and the stilettos – oh, I’m such a hoarder!

JIM:

I don’t think you’d have recognised us in those days. It was flower-power time. I had rather elegant sideboards [FRANCES: and very black hair] while Frances had long hair, huge horn-rimmed glasses and wore full-length flowing dresses.

FRANCES:

Talk about your “modest length” – they went right down to my ankles. You won’t be surprised to hear that I’ve still got one of my flowing dresses in the wardrobe too and every now and then I pull it out and wish I could still get into it.

JIM:

I think it was quite a shock for “A NICE TYPE OF GEL” like Frances to get mixed up with the folk scene. I remember on one occasion we were recording a session with The Dubliners – huge hairy Irishmen. It was just after lunch when they came into the studio – and they’d had a good lunch. Frances went out of the control room, where we were sitting, and into the studio to try to get the titles of the songs they were going to sing.

This immediately turned into an argument among the Dubliners as to what they were going to sing, and there was this great angry group of half-cut Irishmen shouting and yelling at each other with Frances bobbing up and down on the edge of the scrum, saying “Excuse me…” and “I wonder if we could get on…”.

Just as they were about to come to blows, Luke Kelly turned and saw Frances, turned back to the others and said: “Will you for f***’s sake shut up and let the woman speak? What were you saying, Frances?”

FRANCES:

Around that time, Jim and I worked with Peter Sarstedt – an up and coming young singer/songwriter who shot to fame with a song called “Where Do You Go to (My Lovely)?” – I’m sure some of you remember it?

I produced Peter’s radio series and Jim presented it.

Peter’s manager was selling him as a moody – rather ethereal character – not really of this world. Peter and manager arrived in Broadcasting House and Peter went through to the studio to tune up. His manager told me that “Where Do You Go To (My Lovely)?” was such a personal song that Peter had to have all the lights out when he sang it. The studio was duly plunged into darkness. The manager then asked me to come through to meet our star.

What the manager didn’t know was that Peter and I used to live opposite each other in Norbury Crescent and went to Winterbourne Primary school together. When Peter saw who was producing the programme all the lights were back on and we got on with it, just like any other recording!

JIM:

In 1970 we felt there was room for a programme reflecting all the folk activity that was going on at that time. There were over a thousand folk clubs, mostly in backrooms of pubs all over the country. Folk dancing was enormously popular and there were Morris dance sides leaping up and down all over the place.

FRANCES:

We came up with the idea of a programme which brought all these things together, it was called Folk on Friday and thanks to Jim’s immense knowledge of the folk scene it was a smash hit.

JIM:

We’ve still got a copy of a long feature about the programme which was in She magazine. There’s a wonderful photo of Frances with those great big glasses and long hair half covering her face. She’s staring soulfully into the camera and the caption says: “THE EARTH MOTHER OF FOLK”.

FRANCES:

We did a lot of touring round the country for the programme, and one occasion I remember in particular was when we were going up to Bury in Lancashire to record at the folk club there. Bury is very close to a large, desolate area called Pendle Hill, reputed to be a centre of witchcraft.

As we were a bit early for the club we stopped on Pendle Hill for a breather and my PA, Judy, who was with us in the car, decided to go off for a walk. And she didn’t come back. It was a very misty afternoon and beginning to get dark. So Jim went off to look for her – and he didn’t come back either.

I was still a junior producer at this time and my one thought was how I was going to explain to the Head of Radio 2 that I’d lost my entire staff on a witch-infested hill in Lancashire.

JIM:

Eventually, Folk on Friday became Folk on 2 – and twenty-seven years later, it’s still running – and I’m still presenting it. Nowadays it feels more like a pension than a programme. It’s still going out every Wednesday night just after seven on Radio 2. Actually, what are you all doing here? Why aren’t you at home listening? It’s a bit disappointing really…

FRANCES:

The folk years were some of the happiest of my life. But again I could get no further. The BBC did not recognise specialisms in terms of promotion and, if I wanted to get on, I had to get back into mainstream programming.

JIM:

So Frances left me and went off in search of fame and fortune. She made steady progress, rising from junior producer through Producer to Senior Producer while working with a number of star presenters who, sadly, are mostly no longer with us – like Sam Costa.

FRANCES:

Poor Sam. He was a very experienced broadcaster who went back to the forties and Much-Binding-in-the-Marsh. You remember?

JIM:

“Good morning, sir, was there something?”

FRANCES:

And before that he had a successful career as a singer – with Maurice Winnick’s Orchestra and “the sweetest music this side of heaven” – but he still needed a lot of support. He liked to SEE the people he was talking to… And you can’t do that on radio, so the team in the control cubicle became Sam’s substitute audience and we were required to smile at all times as he looked anxiously at us through the soundproof studio glass and to laugh visibly when the punch-lines came.

Sadly Sam was not the most generous of men and often managed to miss his turn to pay for the tea and I can’t say that the technicians liked him. In fact they would delight in looking glum and un-moved by his efforts which would throw Sam into a frenzy. I would be left laughing for everyone and falling down in fits of mirth to re-assure Same that he was slaying the nation. I was a nervous wreck by the end of transmission!

Jim:

Then there was Joe “Mr. Piano” Henderson. Remember his signature tune, “Trudi”? Joe Henderson was another broadcaster who like to do jokes with his gang – his singers.

One of them was a lovely lady called Pat Whitmore and he’d get her doing terrible jokes like:

“What are you doing after the show today, Pat?”

FRANCES:

“I’m going to the library to change my library book, Joe.”

JIM:

“Do you do a lot of reading, Pat?”

FRANCES:

“Yes, I do, Joe.”

JIM:

“Do you like Kipling?”

FRANCES:

“I don’t know, Joe, I’ve never Kipled.”

There were a lot like that and the engineers used to collect them and run a book on the worst of the week. Joe was a very nice and gentle man though and was well liked – that book was just a bit of fun.

JIM:

By 1980 women were breaking through on all fronts. Margaret Thatcher was in Downing Street, Monica Sims in Radio 4 was the BBC’s first woman Network Controller and Frances got her first hospitality cabinet – which was soon withdrawn as an economy measure.

FRANCES:

I had decided to forsake production and had moved into management, with the grand title of Chief Assistant. It meant you were a Controller’s right-hand person and that the network schedule was your particular responsibility.

Initially I was Chief Assistant Radio 2 and later Chief Assistant Radio 4. This was a most stimulating period which I greatly enjoyed and it stretched me quite a bit – not least because I had to schedule the Falklands War.

JIM:

You may wonder how you can schedule a war. Well it was huge challenge and a considerable responsibility because radio tended to be where the news broke first and it was very important to keep the listening millions accurately informed.

FRANCES:

Every day the Controller of Radio 4 – David Hatch – would gather his team together into what he called the War Cabinet and we would examine the possibilities of what the day might hold and try and plan how best to deal with them. It was our proud boast that throughout the war we didn’t lose a single listener – indeed we gained many hundreds of thousands, all coming home to radio as their primary source of information.

JIM:

Frances seemed to spend quite a lot of time dealing with potential disasters. In the days before the Thames Barrier was built there was a real possibility, whenever the tide was high and the wind was in the right direction, of the river breaking its banks and flooding London.

Frances was a member of the Committee whose job it was to run the emergency radio service which would go on air if the disaster should happen. And it actually got quite close on one or two occasions.

FRANCES:

The plan was that a few hours before it happened the Committee would assemble in Broadcasting House, ready to broadcast instructions for the evacuation of London. Of course it might happen at any time of day or night, so we were all given a code word, and they were going to phone us and summon us in from our homes.

JIM:

We were living in Croydon at the time and the BBC gave Frances a bright red pass to show that she was authorised to stay in London as a mass evacuation took place.

Can you imagine? Nine million people, streaming over the bridges – hell bent on putting as much space between them and London as possible –and Frances going the other way, waving her little red pass!

FRANCES:

Well, that’s the BBC for you. It always did put its faith in good documentation!

About ten years ago I left Radio 4 and returned to Radio 2 as the first woman head of the Music Department. Then, on January 1st 1990 – a proud moment for me – I took up my appointment as Controller Radio 2 – only the second woman Programme Controller in the history of the BBC.

JIM:

And what does a Controller do exactly? Well the job description was full of fine words:

- Takes creative responsibility for running Radio 2 within the strategic aims set by the Managing Director.

- Determines the editorial policy for the network and the broad outline of the schedule.

- Commissions programmes to create an appropriate mix of music and speech output for the target audience.

- Seeks out and secures the best talent available.

- Sets and maintains the standards of performance expected from a national public service network.

FRANCES:

In other words, Radio 2 was my baby. I ran the place. I worried about not only what came out of the speakers but about all the artists and staff behind the scenes. I spent a lot of time on dull but necessary things like budgeting meetings, equal opportunities, meeting safety requirements, discussing pay and conditions of service with the unions or trotting along to the House of Commons to explain to the Parliamentary jazz lobby why they couldn’t have jazz all day every day.

But there was also a creative side to the job.

Radio is a very immediate medium and my team and I could come up with an idea and have it on air that day if necessary. In an intensely competitive climate, we all lived by our wits and ideas were our stock in trade so there was plenty of scope for everyone to contribute.

JIM:

For non-listeners, Radio 2 is a 24-hour service, one of the BBC’s five national networks.

It’s the home of entertainment and popular culture and it’s the station of the stars – Terry Wogan, Jimmy Young, Sarah Kennedy – and many, many more. Radio 2 has an audience of some ten million a week. Breakfast is peak listening time but all the shows play to very large audiences.

Listeners are mainly the over-fifties – and most of the presenters are in that age bracket too, the most senior being Alan Keith who presents Your Hundred Best Tunes every Sunday. Alan is eighty-seven and still going strong.

FRANCES:

Perhaps I should say something about the art of the presenter. Let’s take the Radio 2 morning team – Sarah Kennedy, Terry Wogan and Ken Bruce. People often ask me if they work from scripts – is everything they say written down?

Well it certainly is NOT. They live by their wits and their wit.

Not a word is written down. All they have to work from is a running order – a list of records and an indication of where the news, weather and traffic reports should come. Add a pile of listeners’ letters and that’s it, they’re on their own.

They sit in a little studio in Broadcasting House with just a technician for company. The red light comes on. They open their microphone and off they go into the unknown – it’s like walking a tightrope for two hours every morning.

JIM:

Then there are other sort of programmes which are more complex – the sort of thing handled by Jimmy Young and John Dunn with interviews and features, all invariably done “live”.

They do have some researchers working for them but they’re really thinking on their feet the whole time and have the art of asking the question that the listener wants to ask – of a whole variety of guests, some experienced – like politicians – others who’ve never broadcast before but have a good story to tell if you can get it out of them.

John Dunn is arguably the best interviewer on radio and it’s because he really works at it. If you’ve heard his programme you’ll know how good he is with the “mystery voice” contestants – putting them at their ease, and every evening he’ll do maybe six or seven interviews, including half an hour with his “after-six” guest, and when he’s interviewing an author he really does read the book from cover to cover the night before.

FRANCES:

Jim and I have been close friends with John and Margaret Dunn and their family for about thirty years now. We used to live close to each other in Croydon and John and I share the same star-sign

We’re both Pisceans – fishes – and we all go out every year without fail for a fishy lunch for our birthdays. We have one coming up soon.

This friendship came about because I used to produce John light years ago when we were both new to radio, but a really close relationship between an artist and a Controller is very much the exception rather than the rule. It’s impossible to be close and to be the boss. For a start you never know when you’re going to have issue a reprimand of some kind or indeed to fire someone – an unpleasant duty that I’ve had to face many times in my career… and, without question it’s much worse when it’s a friend.

JIM:

Nevertheless, Frances was always as close as was practical with her presenters. Visiting them in the studios at all hours of the day and night and generally encouraging them to give of their best. Sending them birthday cards – anyone who knows Frances knows she’s the birthday card queen – and hand-written notes about their performance. It was very nice for them but really boring for me – she always had the radio on at home, listening with half an ear and making notes – even when she had to get out of bed in the middle of the night she’d turn the radio on for a couple of minutes to find something she liked – or didn’t, which used to frighten the life out of the overnight presenters.

But sometimes the Controller has to be even closer than a friend and had to keep secrets too – as was the case with a much loved early morning presenter who you may remember – the late Ray Moore.

FRANCES:

Yes… Ray used to get the early risers on their feet with his show which started at the ungodly hour of 5.00 am and finished at 7.00. We always got on well and from time to time I’d go in early and have breakfast with him but, other than that, he didn’t appear much in daylight hours because he’d be finished and off home by the time most people were just getting up.

One day he rang the office and asked to see me. He didn’t say why. To my shame I kept him waiting a few minutes because I was tied up in a meeting and when he came in he was certainly not his cheery self. He didn’t beat about the bush. He told me he had inoperable cancer of the throat.

It was a terrible moment and we just put our arms round each other and stood holding each other tight in the middle of the office. When we’d recovered a little, Ray said he didn’t intend to take any treatment because chemotherapy would destroy his voice and he was a broadcaster. Not to be able to speak was something he couldn’t countenance. He intended to broadcast until the end which was likely to be in about a year’s time. Meanwhile he didn’t want anyone to know – would I keep his secret. Of course, I did. But it wasn’t easy.

Sadly the doctors were right and Ray died almost a year to the day after our conversation. He remains a great loss.

JIM:

For Frances, no two days as Controller were the same. And life was always full of surprises. One day she had a phone call from a member of staff who wanted to come into the office at eight in the morning so no-one would see him visiting her. As there were a couple of vacancies at the time in which he might have been interested – she assumed that he wanted to talk privately about his career.

FRANCES:

Not a bit of it. When Chris – who was in his late thirties – arrived at the appointed hour one dark winter’s morning, it was to tell me that he had decided to become a woman. He had a date for the operation and he wanted to warn me that next time I saw him he’d be wearing a dress and high heels and would I please call hm Christine! It takes all sorts and you get most of them at the BBC!

My staff tended to be young and enthusiastic and full of ideas. They worked hard but they played hard too and one day my Marketing Manager came to see me to say that he’d found a particularly good candidate for a researcher vacancy and could I spare five minutes of my time to meet this chap.

Well, I was busy but I said I would – at which point my office door flew open and in came – not a would-be researcher but Mr. Blobby! The staff had set me up and were hot on his heels with a video camera filming the look on my face as Mr. Blobby ran up and gave me a big hug and then ran round the office emptying my in tray on the floor, throwing papers in the air and generally wreaking havoc! As you may guess, I still have that video…

JIM:

Strangely the main problem that faces the Controller of Radio 2 isn’t dealing with the staff or the artists – (FRANCES: Or Mr. Blobby) It’s dealing with the listeners… Radio 2 is hugely popular with a very conservative audience, utterly opposed to any sort of change.

It’s been said that radio is the friend in the corner of the room – and that’s certainly how listeners view Radio 2. They look upon the presenters as personal friends and any attempts to move programmes or people meet with fierce resistance.

FRANCES:

I once replaced two popular Sunday presenters – Benny Green and Allan Dell – with a Gilbert and Sullivan season… just for a few weeks. Their elderly fans marched on Broadcasting House with placards and formed a picket line. The pictures in the next day’s papers showed a group of dear old ladies and gentlemen waving banners which read “LINE IS OUT OF ORDER”. It was a sobering sight.

So I used to grit my teeth and make changes from time to time and I was roundly abused for my pains. Hate mail is common – the strangest people lurk out there in radio land. I’ve lost count of the number of letters which began “You cow…” or “Are You completely mad….” and I’ve received pictures of myself, cut from the papers, with my eyes carefully poked out. You get used to it in the end.

I had a very elaborate “with sympathy” card and – when I opened it – a listener had written “with deepest sympathy on the death of your brain cells”… Another assured me that “in our household, your name is synonymous with Bin-liner”. It’s all charming stuff.

JIM:

Letters containing actual threats go to the Investigators Office (the Corporation’s Security department). They take them very seriously as there are some real nutters out there. However, it’s quite difficult to take the Investigator himself seriously because he rejoices in the name of Protheroe Gotobed!! (The Corporation’s Medical Officer at one time was a lady who rejoiced in the name of Dr. Fingret.)

I think Frances became more of a target for insults because she is a woman. She had trouble with a stalker for instance – a most chilling looking man who used to send her flowers and long registered letters and would hang around outside the building waiting for her to go home.

Then there was someone out there who kept filling in small ads in her name.

FRANCES:

Yes – it started with the delivery of an unwanted hearing aid … I suppose sending a hearing aid to a radio Controller of whom you don’t approve is quite funny in a twisted sort of way. But then it went on and I’d get several calls a day from insurance salesmen, double glazing firms and people who wanted to deliver concrete to my home address. They never did find out who was doing it even though the investigator tracked down the pillar box from which the requests were posted. That felt a bit weird as this particular hate campaign went on for more than five years.

JIM:

One of the problems with listeners is that they don’t always listen – and then they get hold of the wrong end of the stick. An irate lady in Worksop sent Frances a letter complaining at length about the lyrics of a song played on Radio 2 which she found VERY offensive and racist. She complained vehemently that the song contained the line “keep away from coloured boys” – a slur, she said, by the BBC on today’s pluralistic society.

FRANCES:

Well, of course I checked. No such words were broadcast. The song was an old twenties hit – “Button Up Your Overcoat”. Do you know it? And the line to which she took offence was actually:

(SPEAKS) “Keep away from COLLEGE boys when you’re on a spree”

BOTH SING:

“Take good care of yourself, you belong to me …”

I sent her a nice letter with a copy of the words – but I never got an answer.

JIM:

Some letters come under the heading of pitfalls – others are definitely pleasures.

FRANCES:

A gentleman who signs himself Norm was a regular correspondent.

He thought he was Garfield, the cartoon cat. He used to cut out Garfield strips, Tipp-Ex out the words in the balloons and make Garfield address me by inserting his own texts. Garfield liked Radio 2 and often sent me Belgian chocolates which I never ate, just in case he changed his mind!

JIM:

Another regular who signed himself SCRIBE was of a biblical bent:

“And it came to pass that the lowly listener took up his quill and directed a missive to the High Priestess – Frances – being a woman of the tribe of the BBC…” and so on. Scribe lives in Leeds – we stay away from Leeds, even now.

Then there were the poets. Mr. S lived in Hull and addressed Frances thus:

For she doth teach the torches to burn bright

And entertains me late into the night

With harmony, and melody and mirth

On Radio 2 – the greatest show on earth”

FRANCES:

Shakespeare he ain’t but he meant well.

I may occasionally smile at the listeners wilder excesses but the greatest pleasure of all was getting it right for them. Seeing a new idea take off and become part of national life. There are also great rewards at special times of the year, like Christmas when the radio voices are family to those who live alone.

I’d like to finish with one particularly touching letter that brought that home to me.

It was from a lady in Ipswich who wrote “Since I became a widow I have Radio [2] on all the time. You see Radio 2 is my friend – my best friend, next to my husband”

Who could possibly ask for more than to be someone’s best friend?

Thank you.

©Frances and Jim Lloyd. Reproduced by permission. Not to be reproduced elsewhere without the written permission of the copyright holders.