*******************************************************************************************************************************************

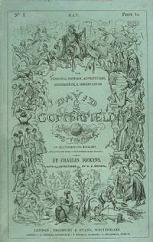

Charles Dickens: David Copperfield / Great Expectations. Palgrave Macmillan Analysing Texts series

David Copperfield and Great Expectations are two of Dickens’s most popular novels. Both are examples of the Bildungsroman, the novel of personal development and education by life, but they do not simply take over an already established form – rather, they enlarge and enrich ideas of what the Bildungsroman can encompass. Both have first-person narrators who look back on their experiences as children and young men from a later perspective, employing sophisticated adult language in their descriptive prose, withholding information to create suspense and produce dramatic climaxes, and moving between vivid recreation of their earlier experiences and more distanced views. Both have characteristic Dickensian qualities: an eloquent command of language, in terms of sentence structure, punctuation, rhythm, imagery and symbolism; complex plots packed with twists, turns, complications and surprises; a rich generic mixture which weaves into the Bildungsroman elements of comedy, tragi-comedy, realism, romance, fairy tale, fantasy, melodrama, gothic fiction and thriller; obsessive, grotesque and eccentric characters who incarnate extreme psychological states linked to key elements of Victorian society; vividly realized settings - landscapes, cityscapes and interiors - which echo and amplify the emotional states and ethical and social issues the novels explore; an emotional and tonal range which includes joy, laughter, love, loss, terror, sublimity, pathos, and pain; and a concern with the proper way to live one’s life and organize society. Both novels powerfully portray isolated childhoods in which the protagonists suffer physical and psychological violence from some of those who should care for them. Both trace patterns of upward mobility as the protagonists achieve greater prosperity and social status. Both move between rural settings close to river and sea and the metropolis of London. Both show their protagonists experiencing shocks, setbacks and losses which culminate in breakdowns from which they eventually make some some kind of recovery.

There are also marked contrasts between the two novels, however. The tone of David Copperfield is exuberant, its narrative manner digressive and theatrical; the tone of Great Expectations is comparatively chastened and its narrative is more strongly focused on characters and events which contribute to the exposition of its plot and the exploration of its themes. In David Copperfield the narrator often makes the reader aware that he is writing from a later perspective, looking back, remembering and recreating; in Great Expectations the narrator reminds the reader of this less often. Both David and Pip suffer many vicissitudes from childhood onwards; but David eventually becomes a successful writer and, after losing his first wife and loved friend, a happily married man with children; Pip, after the confiscation of his fortune, pursues a modest business career in the colonies, stays single, and faces an uncertain matrimonial future at the famously ambiguous end of the novel.

Part I of this book analyses key passages from the text of David Copperfield and Great Expectationsz and explores the ways in which they use the resources of language to develop their novels’ themes. It aims to build up an increasingly rich understanding of each novel, and of the comparisons between them, which starts from, and returns to, the details of the texts.

Part II provides an account of Dickens's life, a survey of the historical, cultural and literary contexts of his work, samples of significant criticism and suggestions for further reading.

*******************************************************************************************************************************************

Anatomies of Melancholy

Recent decades have seen a proliferation of discourses about depression in a variety of genres, including autobiographical accounts, self-help manuals and biomedical, psychotherapeutic and sociogical studies. This book begins with an examination of Robert Burton's great Renaissance compendium, Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) and traces the development of discourses about depressive states of mind from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century, exploring the range of ways in which 'depression' has been understood and the philosophical, psychological, cultural, social and political questions these understandings pose.

*******************************************************************************************************************************************

Work in Progress